It was 1987. General K. Sundarji was in Pune, briefing senior Southern Command officers on the Fourth Pay Commission, when a lowly captain asked an uncomfortable question. He wanted to know why his basic had actually gone down, after the rank pay was introduced. There was a buzz in the room. The chief told the captain to meet him separately, he would explain the issue.“I didn't seek private audience later. I was too junior,” chuckles Major A.K. Dhanapalan (retd). “I actually had no business rubbing shoulders with senior officers that day, except that I was operating the computer for the conference. But I hadn't got it wrong. I was right, bang on.”

The Engineers officer chanced upon the anomaly when he was asked to work on preparing the pay fixation of defence civilian setups, like Military Engineering Service, on the Fourth Pay Commission template. “That year, the commission introduced a rank pay for defence officers between the ranks of captain to brigadier, which was 0200 at captain rank. But what it actually did was deduct the same amount from the basic pay and give it as rank pay. Since all emoluments are linked to basic, not only was there no net gain, we were actually losing out,” Dhanapalan explains. He redid his calculations several times till he was convinced the government had tricked the defence officers. “I wanted to take the matter to court, but I was in Pune and the High Court in Mumbai. Then, I got posted to Udhampur, and the High Court was in Jammu. Next, I was transferred to Port Blair....” Dhanapalan finally got his opportunity on being posted to Kochi in 1995. His office was close to the Kerala High Court; it was time to make that move.

His colleagues were shocked at his daring. His advocate, too, was not convinced. The court, however, understood and ruled that the Union of India should pay the rank pay arrears and an interest of 6 per cent. The matter went on appeal and a division bench of the court upheld the judgment. The government took the matter to the Supreme Court but had to eat humble pie when, in 2006, the court rejected its plea. He did not stop there. The arrears, while welcome, were not his goal. His aim was to alert defence personnel not to be lulled into complacency by the “you are being looked after” attitude of the establishment. So he photocopied the verdict and posted them to officers and clubs he had addresses of. “That itself cost me a bomb,” he recalls. One such letter reached Colonel B.K. Sharma.

Sharma was the first officer to do motorcycle daredevilry in the Republic Day parade in 1978. Post-retirement, he realised it was daredevilry time again, this time to take on the government for which he had once fought. He circulated copies of the judgment in canteens and clubs. Knowing there was strength in numbers, some retired officers got together and registered Retired Defence Officers' Association (RDOA) and filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court in 2007. Meanwhile, across India, officers were litigating for the same demand, and all the cases were finally clubbed together before a division bench of Justices Markandey Katju and R.M. Lodha.

“We had not bargained for the level of resistance from the government. Instead of conceding gracefully, they tried repeatedly to stonewall us,” says Sharma. When in 2010, the bench ruled that it agreed with the reasoning of the Kerala High Court that rank pay be paid retrospectively, with 6 per cent interest, the government filed a transfer petition before a bench of three judges. The three service chiefs recommended to the solicitor general to withdraw the litigation and honour the judgment. The defence ministry, however, pressured the chiefs to withdraw their written communique. In a rare show of defiance, the chiefs stood their ground. The RDOA had to file an RTI to confirm the service chiefs' stance on the matter. “They used every tactic, from pleading inability to meet the financial burden to the solicitor general not appearing in court, due to which proceedings would get postponed,” recalls Sharma. “This summer, when the court fixed the last hearing day on September 4, we actually wrote to the law ministry that so many officers had already died in the last 26 years. Delaying justice was not fair, so either they withdraw the special leave petition or ensure the solicitor general be present in court on September 4.”

The final hearing was a marathon session. The government made a last ditch plea that interest be paid only to litigants. The court refused. However, it reduced the date of calculation of interest from 1986 to 2006 at 6 per cent, ordering that it be paid within 12 weeks. “This is a big victory,” says RDOA advocate Aishwarya Bhati. “It gives a shot in the arm to all other cases that the defence personnel have been fighting.” According to RDOA, over 45,000 officers, retired and serving, will benefit, and it will also impact pensions and widow pensions. The amounts, Sharma calculates, will range from around 06 to 01 lakh, depending on length of service and rank held. The government claims it is a burden of 01,600 crore. “It isn't about money. We fought on principle and we have won our prestige,” says Sharma, but admits being flooded with congratulatory calls, all of them with the suffix, “Mujhe kitna milega? (How much will I get?)”

How did only Dhanapalan get wise to the anomaly? “Faujis are great at protocol, discipline and a hundred other virtues. Studying payslips isn't among those, unfortunately. They usually don't question what goes to the bank, or do the sums themselves,” says Dhanapalan. There are many other issues with defence pay and entitlements, but defence personnel say the government is changing tactics. Instead of risking its decisions being challenged in court, it now procrastinates.

The Sixth Pay Commission anomalies are an example. Last heard, a four-member committee headed by the cabinet secretary was appointed to look into the issue. Then Navy chief Nirmal Verma had expressed anguish at no defence representative being on the committee.

Meanwhile, the man who ignited the spark sits back with a smile. “The government paid arrears only till 1996. I decided not to contest it, as by then, RDOA took up the fight.” There are fears the government might give arrears only till 1996 to others, too. “My mission is accomplished. No longer will faujis take at face value what is given to them. They have learnt to read between lines, ask, and fight for their dues,” says Dhanapalan, getting ready to go to the temple.

(SOURCE - By Rekha Dixit IN THE WEEK)

The basic

pension of all officers who retired before January 1, 2006 will increase between

Rs 1,800 and Rs 3,600. The existing 65 per cent of dearness allowance will also

be admissible over the increased amount. However, this is not as per the OROP

formula.

Despite the increase, officers who retired after January 1, 2006 will get

pensions that are way ahead of those who retired before January 1, 2006. The

other measures on dual family pension and family pension for physically and

mentally handicapped children after marriage have been welcomed.

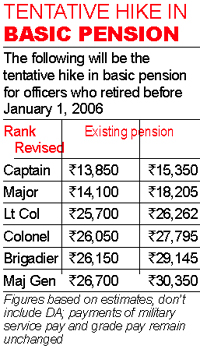

Sources said as per calculations made so far, the following will be the

tentative hike in basic pension for officers who retired before January 1, 2006:

Captain Rs 13,850 (existing) to Rs 15,350 (after hike); Major Rs 14,100 to Rs

18,205; Lt Col Rs 25,700 to Rs 26,262; Colonel Rs 26,050 to Rs 27,795; Brigadier

Rs 26,150 to Rs 29,145 and Major General Rs 26,700 to 30,350. These figures

could be more, depending upon several other factors. This DA would be paid as

per prevailing rates. Other payments of military service pay and grade pay

factored into the pension calculation formula remain unchanged.

Maj General Satbir Singh (retd), vice-chairman of the Indian Ex-Servicemen

Movement, rejected the announcement terming it as “misleading”. “What has been

given, albeit grudgingly, does not even meet provisions of the Armed Forces

Tribunal (AFT) judgments on the matter,” he said in letters shot-off to the

Prime Minister with copies to Defence Minister AK Antony and the three Service

Chiefs. Two summers ago, the General had led a march to Rashtrapati Bhawan where

hundreds of retired personnel returned their medals.

Gurdaspur MP Partap Singh Bajwa and Rohtak MP Deepender Singh Hooda have

welcomed the decision. Bajwa said the remaining demands of serving officers

should be met immediately, while Hooda praised Sonia Gandhi for the move.

Explaining the intricacies of OROP, Maj General Singh said, “OROP means that

defence personnel with the same rank and same length of service must draw the

same pension irrespective of the date of retirement and any future enhancement

would be automatically granted to them. What has been announced is not OROP.”

The hike has come about after a change in calculations. Till now, the pension

for ex-servicemen retiring before January 1, 2006 was calculated as per the

lowest pay in the existing pay band.

The basic

pension of all officers who retired before January 1, 2006 will increase between

Rs 1,800 and Rs 3,600. The existing 65 per cent of dearness allowance will also

be admissible over the increased amount. However, this is not as per the OROP

formula.

Despite the increase, officers who retired after January 1, 2006 will get

pensions that are way ahead of those who retired before January 1, 2006. The

other measures on dual family pension and family pension for physically and

mentally handicapped children after marriage have been welcomed.

Sources said as per calculations made so far, the following will be the

tentative hike in basic pension for officers who retired before January 1, 2006:

Captain Rs 13,850 (existing) to Rs 15,350 (after hike); Major Rs 14,100 to Rs

18,205; Lt Col Rs 25,700 to Rs 26,262; Colonel Rs 26,050 to Rs 27,795; Brigadier

Rs 26,150 to Rs 29,145 and Major General Rs 26,700 to 30,350. These figures

could be more, depending upon several other factors. This DA would be paid as

per prevailing rates. Other payments of military service pay and grade pay

factored into the pension calculation formula remain unchanged.

Maj General Satbir Singh (retd), vice-chairman of the Indian Ex-Servicemen

Movement, rejected the announcement terming it as “misleading”. “What has been

given, albeit grudgingly, does not even meet provisions of the Armed Forces

Tribunal (AFT) judgments on the matter,” he said in letters shot-off to the

Prime Minister with copies to Defence Minister AK Antony and the three Service

Chiefs. Two summers ago, the General had led a march to Rashtrapati Bhawan where

hundreds of retired personnel returned their medals.

Gurdaspur MP Partap Singh Bajwa and Rohtak MP Deepender Singh Hooda have

welcomed the decision. Bajwa said the remaining demands of serving officers

should be met immediately, while Hooda praised Sonia Gandhi for the move.

Explaining the intricacies of OROP, Maj General Singh said, “OROP means that

defence personnel with the same rank and same length of service must draw the

same pension irrespective of the date of retirement and any future enhancement

would be automatically granted to them. What has been announced is not OROP.”

The hike has come about after a change in calculations. Till now, the pension

for ex-servicemen retiring before January 1, 2006 was calculated as per the

lowest pay in the existing pay band. Zeebiz Bureau

Zeebiz Bureau

New Delhi, September 16

New Delhi, September 16